Arts in Florence in the Second Half of the 16th Century

Florentine painting or the Florentine School refers to artists in, from, or influenced past the naturalistic style developed in Florence in the 14th century, largely through the efforts of Giotto di Bondone, and in the 15th century the leading school of Western painting. Some of the best known painters of the before Florentine School are Fra Angelico, Botticelli, Filippo Lippi, the Ghirlandaio family, Masolino, and Masaccio.

Florence was the birthplace of the High Renaissance, but in the early 16th century the nearly important artists, including Michelangelo and Raphael were attracted to Rome, where the largest commissions so were. In function this was following the Medici, some of whom became cardinals and fifty-fifty the pope. A similar process affected afterwards Florentine artists. By the Baroque menstruum, the many painters working in Florence were rarely major figures.

Earlier 1400 [edit]

The earliest distinctive Tuscan art, produced in the 13th century in Pisa and Lucca, formed the basis for later development. Nicola Pisano showed his appreciation of Classical forms equally did his son, Giovanni Pisano, who carried the new ideas of Gothic sculpture into the Tuscan vernacular, forming figures of unprecedented naturalism. This was echoed in the piece of work of Pisan painters in the twelfth and 13th centuries, notably that of Giunta Pisano, who in plow influenced such greats as Cimabue, and through him Giotto and the early on 14th-century Florentine artists.

The oldest extant large scale Florentine pictorial project is the mosaic ornamentation of the interior of the dome of the Baptistery of St John, which began around 1225. Although Venentian artists were involved in the project, the Tuscan artists created expressive, lively scenes, showing emotional content dissimilar the prevailing Byzantine tradition. Coppo di Marcovaldo is said to have been responsible for the central effigy of Christ and is the earliest Florentine artist involved in the project. Similar the panels of the Virgin and Child painted for the Servite churches in Siena and Orvieto, sometimes attributed to Coppo, the Christ figure has a sense of book.

Like works were deputed for the Florentine churches of Santa Maria Novella, Santa Trinita and Ognissanti in the late 13th century and early on 14th century. Duccio'south panel of effectually 1285, Madonna with Child enthroned and 6 Angels or Rucellai Madonna, for the Santa Maria Novella, now in the Uffizi Gallery, shows a development of the naturalistic infinite and form, and may not have been originally intended as altarpieces. Panels of the Virgin were used at summit of rood screens, as at the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi, which has the panel in the fresco of the Verification of the Stigmata in the Life of Saint Francis wheel. Cimabue'southward Madonna of Santa Trinita and Duccio's Rucellai Madonna practice, however, retain the earlier stylism of showing calorie-free on drapery equally a network of lines.

Giotto'south sense of calorie-free would have been influenced past the frescoes he had seen while working in Rome, and in his narrative wall paintings, particularly those commissioned by the Bardi family, his figures are placed in naturalistic space and possess dimension and dramatic expression. A similar approach to light was used by his contemporaries such as Bernardo Daddi, their attention to naturalism was encouraged by the subjects deputed for 14th-century Franciscan and Dominican churches, and was to influence Florentine painters in the following centuries. While some were traditional compositions such every bit those dealing with the order's founder and early saints, others, such as scenes of recent events, people and places, had no precedent, allowing for invention.

The 13th century witnessed an increase in demand for religious panel painting, especially altarpieces, although the reason for this is obscure, early 14th-century Tuscan painters and woodworkers created altarpieces which were more elaborate, multipanelled pieces with complex framing. Contracts of the fourth dimension annotation that clients oft had a woodwork shape in listen when commissioning an artist, and discussed the religious figures to exist depicted with the artists. The content of the narrative scenes in predella panels nevertheless are rarely mentioned in the contracts and may take been left to the artists concerned. Florentine churches commissioned many Sienese artists to create altar pieces, such as Ugolino di Nerio, who was asked to paint a large scale work for the chantry for the Basilica di Santa Croce, which may have been the primeval polyptych on a Florentine altar. The guilds, cognizant of the stimulus that external craftmanship brought, made it easy for artists from other areas to work in Florence. Sculptors had their own guild which held minor status, and by 1316 painters were members of the influential Arte dei Medici e Speziali. The guilds themselves became significant patrons of fine art and from the early 14th century various major guilds oversaw the budget and improvement of individual religious buildings; all the guilds were involved in the restoration of Orsanmichele.

The naturalism developed past the early Florentine artists waned during the third quarter of the 14th century, likely as a consequence of the plague. Major commissions, such as the altarpiece for the Strozzi family (dating from around 1354-57) in Santa Maria Novella, were entrusted to Andrea di Cione, whose work, and in that of his brothers, are more than iconic in their handling of figures and take an earlier sense of compressed space.

Early Renaissance, subsequently 1400 [edit]

Florence continued to exist the most important center of Italian Renaissance painting. The earliest truly Renaissance images in Florence date from 1401, the first year of the century known in Italian equally Quattrocento, synonymous with the Early Renaissance; however, they are non paintings. At that date a competition was held to find an creative person to create a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistry of St. John, the oldest remaining church in the urban center. The Baptistry is a large octagonal building in the Romanesque fashion. The interior of its dome is busy with an enormous mosaic figure of Christ in Majesty thought to accept been designed by Coppo di Marcovaldo. It has three big portals, the primal 1 being filled at that time by a ready of doors created by Andrea Pisano lxxx years before.

Pisano's doors were divided into 28 quatrefoil compartments, containing narratives scenes from the Life of John the Baptist. The competitors, of which in that location were seven young artists, were each to design a bronze panel of similar shape and size, representing the Sacrifice of Isaac. Two of the panels have survived, that by Lorenzo Ghiberti and that by Brunelleschi. Each panel shows some strongly classicising motifs indicating the direction that art and philosophy were moving, at that time. Ghiberti has used the naked figure of Isaac to create a small sculpture in the Classical style. He kneels on a tomb decorated with acanthus scrolls that are also a reference to the fine art of Ancient Rome. In Brunelleschi's console, one of the boosted figures included in the scene is reminiscent of a well-known Roman bronze figure of a male child pulling a thorn from his foot. Brunelleschi's creation is challenging in its dynamic intensity. Less elegant than Ghiberti's, it is more about human being drama and impending tragedy.[1]

Ghiberti won the contest. His first prepare of Baptistry doors took 27 years to complete, after which he was deputed to make another. In the total of 50 years that Ghiberti worked on them, the doors provided a grooming basis for many of the artists of Florence. Being narrative in subject and employing not only skill in arranging figurative compositions but also the burgeoning skill of linear perspective, the doors were to accept an enormous influence on the evolution of Florentine pictorial art. They were a unifying gene, a source of pride and camaraderie for both the city and its artists. Michelangelo was to call them the Gates of Paradise.

Brancacci Chapel [edit]

In 1426 two artists commenced painting a fresco wheel of the Life of St. Peter in the chapel of the Brancacci family, at the Carmelite Church building in Florence. They both were called by the proper noun of Tommaso and were nicknamed Masaccio and Masolino, Slovenly Tom and Little Tom.

More any other creative person, Masaccio recognized the implications in the work of Giotto. He carried frontwards the do of painting from nature. His paintings demonstrate an understanding of anatomy, of foreshortening, of linear perspective, of calorie-free and the report of drapery. Amidst his works, the figures of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden, painted on the side of the arch into the chapel, are renowned for their realistic depiction of the homo grade and of human being emotion. They contrast with the gentle and pretty figures painted by Masolino on the contrary side of Adam and Eve receiving the forbidden fruit. The painting of the Brancacci Chapel was left incomplete when Masaccio died at 26. The work was later finished past Filippino Lippi. Masaccio's piece of work became a source of inspiration to many later painters, including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.[2]

Development of linear perspective [edit]

Paolo Uccello: The Presentation of the Virgin shows his experiments with perspective and light.

During the get-go half of the 15th century, the achieving of the effect of realistic space in a painting by the employment of linear perspective was a major preoccupation of many painters, as well as the architects Brunelleschi and Alberti who both theorised about the subject. Brunelleschi is known to accept done a number of careful studies of the piazza and octagonal baptistery outside Florence Cathedral and it is thought he aided Masaccio in the cosmos of his famous trompe-l'œil niche around the Holy Trinity he painted at Santa Maria Novella.[2]

According to Vasari, Paolo Uccello was so obsessed with perspective that he thought of lilliputian else and experimented with it in many paintings, the best known being the three Battle of San Romano pictures which use cleaved weapons on the footing, and fields on the distant hills to give an impression of perspective.

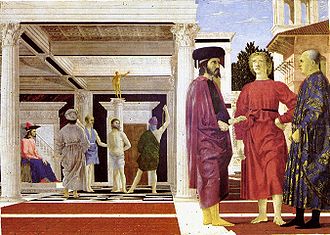

In the 1450s Piero della Francesca, in paintings such every bit The Flagellation of Christ, demonstrated his mastery over linear perspective and also over the scientific discipline of light. Some other painting exists, a cityscape, by an unknown artist, perhaps Piero della Francesca, that demonstrates the sort of experiment that Brunelleschi had been making. From this time linear perspective was understood and regularly employed, such equally by Perugino in his Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter in the Sistine Chapel.[1]

Piero della Francesca: The Flagellation demonstrates the artist'south control over both perspective and light.

Understanding of light [edit]

Giotto used tonality to create form. Taddeo Gaddi in his nocturnal scene in the Baroncelli Chapel demonstrated how low-cal could be used to create drama. Paolo Uccello, a hundred years subsequently, experimented with the dramatic effect of lite in some of his almost monochrome frescoes. He did a number of these in terra verde or "greenish earth", enlivening his compositions with touches of vermilion. The best known is his equestrian portrait of John Hawkwood on the wall of Florence Cathedral. Both hither and on the 4 heads of prophets that he painted around the inner clockface in the cathedral, he used strongly contrasting tones, suggesting that each figure was being lit by a natural calorie-free source, as if the source was an actual window in the cathedral.[three]

Piero della Francesca carried his study of light farther. In the Flagellation he demonstrates a knowledge of how low-cal is proportionally disseminated from its betoken of origin. At that place are two sources of light in this painting, one internal to a building and the other external. Of the internal source, though the light itself is invisible, its position can be calculated with mathematical certainty. Leonardo da Vinci was to carry frontward Piero's work on low-cal.[4]

The Madonna [edit]

The Blessed Virgin Mary, revered by the Cosmic Church worldwide, was particularly evoked in Florence, where there was a miraculous image of her on a column in the corn market and where both the Cathedral of "Our Lady of the Flowers" and the large Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella were named in her laurels.

The miraculous image in the corn market was destroyed past fire, merely replaced with a new image in the 1330s by Bernardo Daddi, set up in an elaborately designed and lavishly wrought awning by Orcagna. The open up lower storey of the building was enclosed and defended as Orsanmichele.

Depictions of the Madonna and Child were a very popular art form in Florence. They took every shape from small mass-produced terracotta plaques to magnificent altarpieces such as those by Cimabue, Giotto and Masaccio. Pocket-sized Madonnas for the dwelling house were the bread and butter work of near painting workshops, often largely produced by the junior members post-obit a model by the master. Public buildings and government offices too often independent these or other religious paintings.

Among those who painted devotional Madonnas during the Early Renaissance are Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Verrocchio and Davide Ghirlandaio. After the leading purveyor was Botticelli and his workshop who produced large numbers of Madonnas for churches, homes, and besides public buildings. He introduced a large round tondo format for thou homes. Perugino's Madonnas and saints are known for their sweet and a number of pocket-size Madonnas attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, such as the Benois Madonna, have survived. Even Michelangelo who was primarily a sculptor, was persuaded to paint the Doni Tondo, while for Raphael, they are amid his about pop and numerous works.

Birthing-trays [edit]

A Florentine speciality was the circular or 12-sided desco da parto or birthing-tray, on which a new mother served sweetmeats to the female friends who visited her later on the nascence. The residue of the time these seem to accept been hung in the bedroom. Both sides are painted, ane with scenes to encourage the mother during the pregnancy, often showing a naked male toddler; viewing positive images was believed to promote the result depicted.

Painting and printmaking [edit]

From around the mid-century, Florence became Italy's leading centre of the new industry of printmaking, as some of the many Florentine goldsmiths turned to making plates for engravings. They often copied the mode of painters, or drawings supplied past them. Botticelli was 1 of the start to experiment with drawings for volume illustrations, in his instance of Dante. Antonio del Pollaiuolo was a goldsmith likewise equally a printer, and engraved his Boxing of the Nude Men himself; in its size and composure this took the Italian print to new levels, and remains ane of the most famous prints of the Renaissance.

Patronage and Humanism [edit]

In Florence, in the later 15th century, most works of fine art, fifty-fifty those that were done as decoration for churches, were generally deputed and paid for by private patrons. Much of the patronage came from the Medici family unit, or those who were closely associated with or related to them, such as the Sassetti, the Ruccellai and the Tornabuoni.

In the 1460s Cosimo de' Medici the Elder had established Marsilio Ficino as his resident Humanist philosopher, and facilitated his translation of Plato and his didactics of Platonic philosophy, which focused on humanity as the centre of the natural universe, on each person'due south personal relationship with God, and on congenial or "ideal" dear every bit being the closest that a person could get to emulating or understanding the beloved of God.[5]

In the Medieval catamenia, everything related to the Classical period was perceived as associated with paganism. In the Renaissance information technology came increasingly to be associated with enlightenment. The figures of Classical mythology began to accept on a new symbolic office in Christian art and in detail, the Goddess Venus took on a new discretion. Built-in fully formed, by a sort of miracle, she was the new Eve, symbol of innocent honey, or even, by extension, a symbol of the Virgin Mary herself. We see Venus in both these roles in the two famous tempera paintings that Botticelli did in the 1480s for Cosimo's nephew, Pierfrancesco Medici, the Primavera and the Birth of Venus.[six]

Meanwhile, Domenico Ghirlandaio, a meticulous and authentic draughtsman and ane of the finest portrait painters of his age, executed ii cycles of frescoes for Medici associates in two of Florence'south larger churches, the Sassetti Chapel at Santa Trinita and the Tornabuoni Chapel at Santa Maria Novella. In these cycles of the Life of St Francis and the Life of the Virgin Mary and Life of John the Baptist in that location was room for portraits of patrons and of the patrons' patrons. Thank you to Sassetti's patronage, at that place is a portrait of the man himself, with his employer, Lorenzo il Magnifico, and Lorenzo's three sons with their tutor, the Humanist poet and philosopher, Agnolo Poliziano. In the Tornabuoni Chapel is some other portrait of Poliziano, accompanied past the other influential members of the Platonic Academy including Marsilio Ficino.[5]

Flemish influence [edit]

From well-nigh 1450, with the arrival in Italy of the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden and possibly earlier, artists were introduced to the medium of oil paint. Whereas both tempera and fresco lent themselves to the delineation of pattern, neither presented a successful way to stand for natural textures realistically. The highly flexibly medium of oils, which could be fabricated opaque or transparent, and immune alteration and additions for days later on it had been laid downwardly, opened a new world of possibility to Italian artists.

In 1475 a huge altarpiece of the Adoration of the Shepherds arrived in Florence. Painted by Hugo van der Goes at the behest of the Portinari family, it was shipped out from Bruges and installed in the Chapel of Sant' Egidio at the infirmary of Santa Maria Nuova. The altarpiece glows with intense reds and greens, contrasting with the glossy black velvet robes of the Portinari donors. In the foreground is a still life of flowers in contrasting containers, ane of glazed pottery and the other of glass. The glass vase lone was enough to excite attention. But the nearly influential attribute of the triptych was the extremely natural and lifelike quality of the three shepherds with stubbly beards, workworn hands and expressions ranging from adoration to wonder to incomprehension. Domenico Ghirlandaio promptly painted his own version, with a cute Italian Madonna in place of the long-faced Flemish one, and himself, gesturing theatrically, every bit one of the shepherds.[1]

Papal commission in Rome [edit]

In 1477 Pope Sixtus 4 replaced the derelict old chapel at the Vatican in which many of the papal services were held. The interior of the new chapel, named the Sistine Chapel in his honour, appears to accept been planned from the start to have a series of sixteen large frescoes between its pilasters on the heart level, with a series of painted portraits of popes to a higher place them.

In 1480, a group of artists from Florence was commissioned with the work: Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli. This fresco bicycle was to depict Stories of the Life of Moses on one side of the chapel, and Stories of the Life of Christ on the other with the frescoes complementing each other in theme. The Nativity of Jesus and the Finding of Moses were side by side on the wall backside the chantry, with an altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin between them. These paintings, all by Perugino, were later destroyed to paint Michelangelo's Final Judgement.

The remaining 12 pictures indicate the virtuosity that these artists had attained, and the obvious cooperation betwixt individuals who normally employed very dissimilar styles and skills. The paintings gave full range to their capabilities as they included a keen number of figures of men, women and children and characters ranging from guiding angels to enraged Pharaohs and the devil himself. Each painting required a landscape. Because of the scale of the figures that the artists agreed upon, in each movie, the landscape and sky accept up the whole upper one-half of the scene. Sometimes, every bit in Botticelli's scene of The Purification of the Leper, there are additional small narratives taking place in the landscape, in this example The Temptations of Christ.

Perugino'due south scene of Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter is remarkable for the clarity and simplicity of its limerick, the beauty of the figurative painting, which includes a self-portrait among the onlookers, and especially the perspective cityscape which includes reference to Peter's ministry to Rome by the presence of two triumphal arches, and centrally placed an octagonal building that might be a Christian baptistry or a Roman Mausoleum.[7]

High Renaissance [edit]

Florence was the birthplace of the High Renaissance, but in the early 16th century the well-nigh of import artists were attracted to Rome, where the largest commissions began to exist. In role this was following the Medici, some of whom became cardinals and even the pope.

Leonardo da Vinci [edit]

Leonardo, because of the scope of his interests and the boggling degree of talent that he demonstrated in so many diverse areas, is regarded equally the archetypal "Renaissance man". But information technology was first and foremost as a painter that he was admired within his ain time, and as a painter, he drew on the knowledge that he gained from all his other interests.

Leonardo da Vinci: The Last Supper

Leonardo was a scientific observer. He learned past looking at things. He studied and drew the flowers of the fields, the eddies of the river, the class of the rocks and mountains, the style light reflected from foliage and sparkled in a gem. In particular, he studied the human form, dissecting xxx or more than unclaimed cadavers from a hospital in lodge to understand muscles and sinews.

More than whatsoever other artist, he avant-garde the study of "atmosphere". In his paintings such as the Mona Lisa and Virgin of the Rocks, he used low-cal and shade with such subtlety that, for want of a better word, it became known equally Leonardo's "sfumato" or "fume".

Simultaneous to inviting the viewer into a mysterious earth of shifting shadows, chaotic mountains and whirling torrents, Leonardo accomplished a caste of realism in the expression of human emotion, prefigured by Giotto but unknown since Masaccio's Adam and Eve. Leonardo's Last Supper, painted in the refectory of a monastery in Milan, became the benchmark for religious narrative painting for the side by side half millennium. Many other Renaissance artists painted versions of the Terminal Supper, just merely Leonardo's was destined to exist reproduced countless times in wood, alabaster, plaster, lithograph, tapestry, crochet and table-carpets.

Autonomously from the direct affect of the works themselves, Leonardo'due south studies of lite, anatomy, mural, and human expression were disseminated in part through his generosity to a retinue of students.[8]

Michelangelo [edit]

In 1508 Pope Julius II succeeded in getting the sculptor Michelangelo to agree to continue the decorative scheme of the Sistine Chapel. The Sistine Chapel ceiling was constructed in such a way that there were twelve sloping pendentives supporting the vault that formed platonic surfaces on which to paint the Twelve Apostles. Michelangelo, who had yielded to the Pope's demands with petty grace, shortly devised an entirely unlike scheme, far more complex both in design and in iconography. The scale of the piece of work, which he executed single handed except for manual assistance, was titanic and took nearly v years to complete.

The Pope's plan for the Apostles would thematically have formed a pictorial link between the One-time Testament and New Attestation narratives on the walls, and the popes in the gallery of portraits.[7] It is the twelve apostles, and their leader Peter as first Bishop of Rome, that make that span. But Michelangelo's scheme went the opposite direction. The theme of Michelangelo'southward ceiling is not God'southward thou program for humanity'due south conservancy. The theme is about humanity's disgrace. It is nearly why humanity and the organized religion needed Jesus.[9]

Superficially, the ceiling is a Humanist construction. The figures are of superhuman dimension and, in the case of Adam, of such beauty that according to the biographer Vasari, it actually looks as if God himself had designed the figure, rather than Michelangelo. Simply despite the beauty of the private figures, Michelangelo has not glorified the human being state, and he certainly has non presented the Humanist ideal of ideal love. In fact, the ancestors of Christ, which he painted around the upper section of the wall, demonstrate all the worst aspects of family relationships, displaying dysfunction in every bit many different forms as there are families.[9]

Vasari praised Michelangelo'south seemingly infinite powers of invention in creating postures for the figures. Raphael, who was given a preview past Bramante afterward Michelangelo had downed his castor and stormed off to Bologna in a temper, painted at least two figures in imitation of Michelangelo'south prophets, one at the church of Sant' Agostino and the other in the Vatican, his portrait of Michelangelo himself in The School of Athens.[7] [x] [11]

Raphael [edit]

With Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, Raphael'south proper noun is synonymous with the Loftier Renaissance, although he was younger than Michelangelo by eighteen years and Leonardo by almost 30. Information technology cannot exist said of him that he greatly avant-garde the state of painting every bit his two famous contemporaries did. Rather, his work was the culmination of all the developments of the Loftier Renaissance.

Raphael had the skillful luck to exist born the son of a painter, and then his career path, unlike that of Michelangelo who was the son of minor nobility, was decided without a quarrel. Some years after his father's death he worked in the Umbrian workshop of Perugino, an excellent painter and a superb technician. His outset signed and dated painting, executed at the age of 21, is the Betrothal of the Virgin, which immediately reveals its origins in Perugino'due south Christ giving the Keys to Peter.[12]

Raphael was a carefree graphic symbol who unashamedly drew on the skills of the renowned painters whose lifespans encompassed his. In his works the private qualities of numerous dissimilar painters are fatigued together. The rounded forms and luminous colours of Perugino, the lifelike portraiture of Ghirlandaio, the realism and lighting of Leonardo and the powerful draughtsmanship of Michelangelo became unified in the paintings of Raphael. In his short life he executed a number of large altarpieces, an impressive Classical fresco of the ocean nymph, Galatea, outstanding portraits with two popes and a famous writer among them, and, while Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a series of wall frescoes in the Vatican chambers nearby, of which the School of Athens is uniquely significant.

This fresco depicts a meeting of all the nearly learned ancient Athenians, gathered in a m classical setting around the central figure of Plato, whom Raphael has famously modelled upon Leonardo da Vinci. The heart-searching figure of Heraclitus who sits by a large block of stone, is a portrait of Michelangelo, and is a reference to the latter'due south painting of the Prophet Jeremiah in the Sistine Chapel. His own portrait is to the correct, beside his teacher, Perugino.[13]

But the principal source of Raphael'due south popularity was not his major works, merely his pocket-sized Florentine pictures of the Madonna and Christ Child. Over and over he painted the aforementioned plump calm-faced blonde woman and her succession of chubby babies, the near famous probably being La Belle Jardinière ("The Madonna of the Beautiful Garden"), now in the Louvre. His larger piece of work, the Sistine Madonna, used as a design for countless stained drinking glass windows, has come up, in the 21st century, to provide the iconic image of two pocket-size cherubs which has been reproduced on everything from newspaper tabular array napkins to umbrellas.[14] [15]

Early Mannerism [edit]

The early on Mannerists in Florence, especially the students of Andrea del Sarto such as Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, are notable for elongated forms, precariously balanced poses, a collapsed perspective, irrational settings, and theatrical lighting. As the leader of the Start Schoolhouse of Fontainebleau, Rosso was a major forcefulness in the introduction of Renaissance style to France.

Parmigianino (a educatee of Correggio) and Giulio Romano (Raphael'southward caput assistant) were moving in similarly stylized aesthetic directions in Rome. These artists had matured under the influence of the High Renaissance, and their style has been characterized as a reaction to or exaggerated extension of information technology. Instead of studying nature direct, younger artists began studying Hellenistic sculpture and paintings of masters past. Therefore, this style is oft identified as "anti-classical",[16] notwithstanding at the time it was considered a natural progression from the High Renaissance. The earliest experimental phase of Mannerism, known for its "anti-classical" forms, lasted until about 1540 or 1550.[17] Marcia B. Hall, professor of art history at Temple University, notes in her book After Raphael that Raphael's premature death marked the beginning of Mannerism in Rome.

Later Mannerism [edit]

Bronzino (d.1572), a student of Pontormo, was mostly a courtroom portraitist for the Medici court, in a somewhat frigid formal Mannerist style. In the same generation, Giorgio Vasari (d. 1574) is far better remembered as the author of the Lives of the About Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, which had an enormous and lasting effect in establishing the reputation of the Florentine Schoolhouse. Just he was the leading painter of history painting in the Medici court, although his work is at present generally seen as straining after the affect that Michelangelo's piece of work has, and failing to accomplish it. This had get a common fault in Florentine painting by the decades after 1530, equally many painters tried to emulate the giants of the Loftier Renaissance.

Bizarre [edit]

By the Baroque period, Florence was no longer the most important centre of painting in Italia, but was important still. Leading artists built-in in the city, and who, different others, spent much of their careers there, include Cristofano Allori, Matteo Rosselli, Francesco Furini, and Carlo Dolci. Pietro da Cortona was built-in in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and did much work in the city.

See also [edit]

- Venetian school

- Bolognese School

- Lucchese School

- Schoolhouse of Ferrara

- Sienese School

References [edit]

- ^ a b c R.Due east. Wolf and R. Millen, Renaissance and Mannerist Art, (1968)

- ^ a b Ornella Casazza, Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel, (1990)

- ^ Annarita Paolieri, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, (1991)

- ^ Peter Murray and Pier Luigi Vecchi, Piero della Francesca, (1967)

- ^ a b Hugh Ross Williamson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, (1974)

- ^ Umberto Baldini, Primavera, (1984)

- ^ a b c Giacometti, Massimo (1986). The Sistine Chapel.

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, (1568), 1965 edition, trans George Bull, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044164-6

- ^ a b T.L.Taylor, The Vision of Michelangelo, Sydney Academy, (1982)

- ^ Gabriel Bartz and Eberhard König, Michelangelo, (1998)

- ^ Ludwig Goldschieder, Michelangelo, (1962)

- ^ Diana Davies, "Raphael", Harrap'south Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, (1990)

- ^ Some sources identify this figure as Il Sodoma, but information technology is an older, grey-haired man, while Sodoma was in his 30s. Moreover, it strongly resembles several self-portraits of Perugino, who would have been about sixty at the fourth dimension.

- ^ David Thompson, Raphael, the Life and Legacy, (1983)

- ^ Jean-Pierre Cuzin, Raphael, his Life and Works, (1985)

- ^ Friedländer 1965,[ page needed ].

- ^ Freedberg, Sidney J. 1993. Painting in Italian republic, 1500–1600, pp. 175-177, tertiary edition, New Haven and London: Yale University Printing. ISBN 0-300-05586-2 (fabric) ISBN 0-300-05587-0 (pbk)

Further reading [edit]

- "Florence Art life and system", The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Ed. Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford University Printing, 2001. ISBN 0-xix-866203-3.

- Pope-Hennessy, John & Kanter, Laurence B. (1987). The Robert Lehman Collection I, Italian Paintings . New York, Princeton: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in association with Princeton University Press. ISBN0870994794.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) (see alphabetize)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florentine_painting

0 Response to "Arts in Florence in the Second Half of the 16th Century"

Post a Comment